The Path to Payment Reform

The Path to Payment Reform

More than 50 percent of all payments to medical providers – health systems, physicians and other care providers – are made by federal, state and local government funds1. These costs have accelerated to reflect an aging population and price inflation, and are projected to account for nearly 20 percent of the gross domestic product in the United States by 2024 — making it the most costly in the world2. With health outcomes not notably improving alongside greater expenditures, health scholars have for years posited that real improvements can come only from a culture of safety and patient-centered care with reimbursement based on high quality performance. Health care delivery transformation and payment reform go hand in hand. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expressly intends to utilize its current authority to increasingly weave together separate payment strands into a fabric that supports and rewards high performance health care through value-based payment (VBP) programs. CMS has been charged with the successful execution of health care reform laws through articulated policy directives and payment strategies.

Three federal initiatives that have grounded these policies in planning and purpose are:

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA), with its stated imperative to move away from fee-for-service (FFS) payments into value-based purchasing and clinical care model innovation.

- The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 20153 introduced the Quality Payment Program (QPP) to the realm of health care reform. The QPP initiated important changes to the payment structure for Medicare providers via two key paths that promote payment for value and better care: Merit-Based Incentive Payment Systems (MIPS) and Alternative Payment Models (APMs)4.

- 1115 Medicaid waivers that allow states to utilize Medicaid dollars to incentivize local health providers to move away from volume-based fragmented services and into community-wide, value-based high-performance systems. Washington and New York are two states looking to use 1115 Medicaid Transformation Waiver funds as a catalyst to develop the required infrastructure and program changes that promote financial viability in a VBP structure.

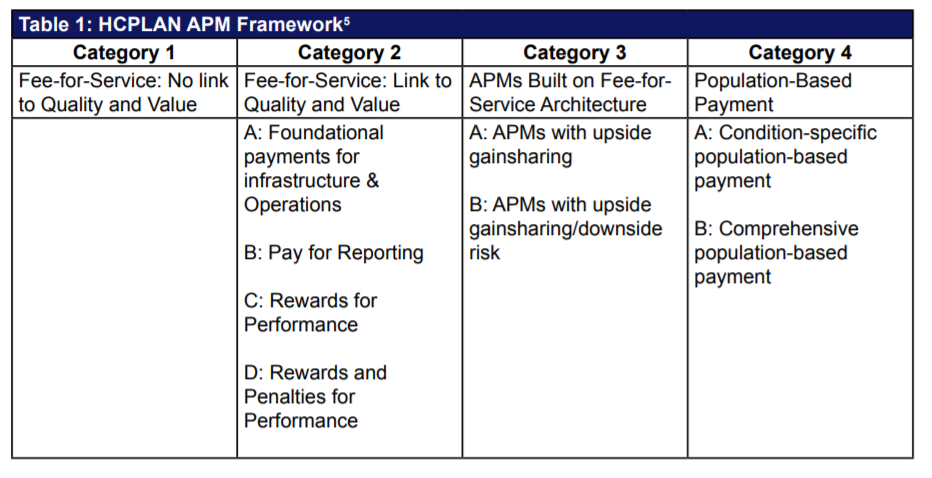

CMS continues to focus on alternative payment models for payment reform and the transition to value. VBP initiatives include the Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and Pioneer ACOs, Bundled Payment for Care Improvement and the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, among others. These and other similar VBP initiatives are built on the foundation of the Alternative Payment Model Framework (see Table 1), articulated by the Health Care Payment and Learning Network (HCPLAN), which defines four categories to track progress of payment reform across the nation. These categories are used as standards in the New York and Washington State VBP roadmaps. This article will introduce and discuss how states can leverage 1115 Medicaid Waiver funds to incentivize providers in identified regions and networks to move towards VBP and provide an overview and comparison of the key concepts in the VBP roadmap for the states of New York and Washington.

1115 Medicaid Transformation Waivers as Catalysts for Value-Based Payment Programs

The Section 1115 Waiver authority allows CMS to permit and support innovative approaches for Medicaid “service delivery, coverage of expansion populations and new types of service, and payment approaches intended to align financial incentives with program improvement goals.”6 In all states with waiver programs, there must be a source of state or local permissible health funds to match federal dollars.

Most recent state 1115 Waivers include a Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Program component, and the most recent DSRIP waivers have been approved in California, Texas, and New York. Washington State is also currently in the application process for an 1115 Waiver and associated funds to implement a five-year DSRIP-program to expedite health system transformation across the state.

Originally, DSRIP initiatives were more narrowly focused on providing supplemental funding for public safety net hospitals and often grew out of negotiations between states and Health and Human Services (HHS) over the appropriate way to finance hospital-based care. Recently, states that have been allocated Medicaid reform dollars are now expected to implement innovative programs that address community needs within identified regions to promote transformation and achieve population health goals for the Medicaid and Uninsured populations. In all DSRIP programs, the state articulates a clear vision for a transformed Medicaid delivery system; then identifies activities intended to transform the delivery system. Providers join together to undertake these transformation activities and the state funds providers based on hitting specified milestones/metrics.

Now, they are increasingly being used to promote a far more sweeping set of state-wide payment and delivery system reforms. As CMS continues to both track and scrutinize the successes and goals of these waivers and DSRIP Programs across states, a VBP component becomes more crucial to support the broader system goals funded via DSRIP funds — promoting sustainability for the models introduced with waiver funding. It is important to note that as states move most of their Medicaid lives into managed care, the goals of these waivers and VBP efforts become even more important to states, health plans and providers. States like New York and Washington already have most, if not all, Medicaid lives enrolled in managed care (see Figure 1).

As states continue to strive for budget neutrality, they continue to push the risk down to participating managed care organizations (MCOs) by capitating them under these programs and making them responsible for flowing funds appropriately to participating providers. In an effort to reduce their own risk, MCOs will gravitate towards high performing providers as more premium dollars are tied to quality outcome scores. Flowing dollars from the state through MCOs reduces the risk and administrative complexity for the state, but from a provider perspective may lead to MCOs holding back more dollars for administrative purposes and setting providers up for more complexity due to the variation in quality, financial and reporting metrics, as well as contract structures for each MCO. In an effort to mitigate this in the transition to VBP, states like New York and Washington have incorporated oversight committees and minimum premium thresholds for provider incentives that MCOs must meet in VBP contractual agreements.

The DSRIP program incentive payments are intended to incentivize providers to develop the required infrastructure to succeed in a pay for performance environment. The outcome measures used to report and track improvement via DSRIP projects are reflective of the quality measures MCOs are currently required to report and the performance improvement plans they are required to develop and implement. Through alignment of DSRIP and VBP contracts, health plans, health systems and IPAs can better prepare providers for long term success under VBP contracts and reduce the administrative burden on both parties. New York and Washington have developed evolving VBP Roadmaps that will serve to guide and support Medicaid providers to align current efforts, additional transformation strategies and 1115 waiver funds with sustainable VBP strategies. New York is also leveraging the 1115 waiver and VBP Roadmap to close readiness gaps in order to successfully push more risk onto providers.

Figure 17: Managed Care Program Highlights – Washington and New York

The Roadmap to VBP: New York and Washington State

Current State

New York’s approved 2014 DSRIP program authorized up to $6.42 billion for reinvestment efforts to align the state’s provider and community-based systems with the goals of VBP. The New York State Roadmap for Medicaid Payment Reform8 released in July 2015 is intended to be a living document that will continue to evolve and support the work of New York state (NYS) toward payment reform. This roadmap details the vision and strategy for alignment of DSRIP efforts managed by Performing Provider System (PPS)9 leads and the transition from FFS to VBP across the State. NYS shared its first (draft) annual VBP Roadmap update in June 2016.

Meanwhile, the Washington State Medicaid Transformation Waiver application was submitted on August 24, 201510 and proposes a $3 billion, five-year demonstration. Washington State seeks to leverage work by Accountable Communities of Health (ACHs)11 to transform health care at the regional and state levels via the 1115 Waiver. A proposal to include the development of a value-based payment roadmap as a milestone in the Special Terms and Conditions (STCs) of the waiver is mentioned in the application, and a preliminary roadmap has been published by Washington State Health Care Authority (HCA) as of June 14, 2016.12

Key Themes and Components of New York and Washington State VBP Roadmaps

Despite the fact that the Washington State VBP Roadmap is still in its early development stages, there are several common themes that are similar to New York State’s latest roadmap. Overarching themes include a preference for patient-centered care that is “accountable” to quality and cost metrics with the expressed goal of increasing “value” to the various stakeholders. Other cross-cutting themes include transparency of process, as well as collaboration among providers, systems and health plans (without violating antitrust laws) through regionalized collaboratives such as PPSs in New York State and ACHs in Washington State. It should also be noted that both states have a percent of premium dollars for MCOs directly tied to quality improvement metrics, one percent premium withhold in Washington and up to three percent in New York managed care programs for non-disabled adults and children. Both states plan to further evolve or increase these current withholds tied to quality; New York is developing a proposal to withhold a certain amount of money from premiums to create a quality incentive pool for MLTC plans and Washington expects the quality withhold to gradually increase each year until it reaches three percent in 2021. VBP efforts will support this transition and allow MCOs to share more dollars with high performing providers as they receive these withhold dollars for positive quality results.

Key components of both VBP roadmaps include:

- Standardization of performance metrics to reduce administrative burden on MCOs and providers/contractors: There is a specific focus on alignment with DSRIP objectives and measures in both state VBP roadmaps.

- Changes to MCO contracts: NYS has outlined guidelines, will update the Medicaid Managed Care Model Contract, and will implement a contract review process for VBP contracts; Washington State will use a third-party assessment organization to review and validate payer-provider arrangements under Medicaid to measure status of these arrangements.

- Incorporation of social determinants of health (SDH) and integration of non-traditional (non-clinical) providers in MCO contracts, such as community-based organizations (CBOs): Both states discuss the importance of SDH inclusion in VBP arrangements; New York State will incorporate incentives for providers who successfully address SDH in VBP strategies and contracts.

- Additional funding pools available for high performers to further incentivize quality care: NYS will reward high performers via dollars from pools labeled High Performance Funds and Additional High Performance Funds, while Washington State will develop the Challenge Pool and Reinvestment Pool for similar incentive purposes.

In addition to the key themes outlined above, a key component of NYS not currently outlined in the Washington State roadmap is the Clinical Advisory Groups (CAGs) that have been developed. These CAGs were created to inform and review the identified care bundles and subpopulations most relevant to NYS Medicaid. These work groups will make recommendations on quality measures, data and support requirements for success, and address other details for VBP arrangements. The current CAGs in NYS have been developed for the six subpopulations: maternity, chronic heart/diabetes, behavioral health, HIV/AIDS, managed long term care (MLTC), and intellectually/developmentally disabled (I/DD). As of July 2016, the CAGs have developed draft VBP Recommendation Reports and Playbooks for the maternity care, HIV/AIDS, and health and recovery plan (HARP) subpopulations. Additional reports and playbooks will continue to be developed by CAGs to guide future VBP contracting strategies, specifically around related outcomes to measure successful improvement. The Washington State roadmap does not currently include a CAG or other work group component, but it is likely that this will be introduced in a more detailed roadmap in the future.

VBP Roadmap Levels and Goals for New York and Washington State

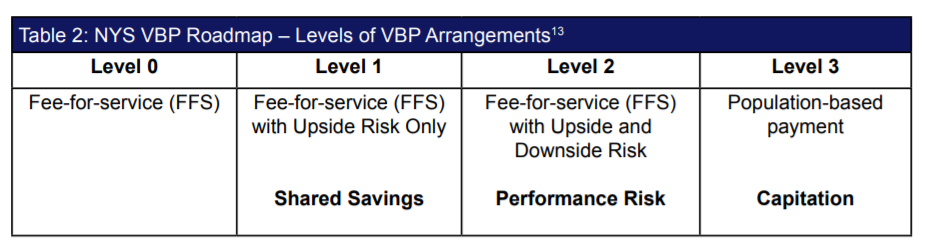

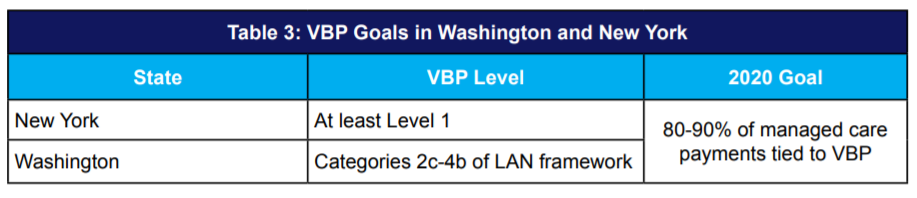

New York State’s VBP Roadmap identifies four VBP arrangement levels that align with the LAN APM categories and will serve as the guide to track progress towards VBP arrangements goals across NYS (see Table 2). Progress in Washington will be tracked using categories 2c-4b of the LAN APM Framework (see Table 1)14.

Both New York State and Washington State have similar VBP achievement goals in 2020 (Table 3).

In its efforts to expedite VBP efforts and further incentivize providers ahead of the game and ready and willing to take on more risk, NYS has included a voluntary VBP Innovator Program in its roadmap. The providers that are eligible for this program are those providers that are eager and ready to enter into level 2 or 3 VBP arrangements, most of which will already have experience in such arrangements. The state’s goal is to include total care for total population and subpopulations in this program while the Department of Health and the Department of Financial Services (DFS) monitors performance and provides oversight. PPSs or provider groups that meet the outlined criteria and provide total population health for all costs of care will be eligible to receive up to 95 percent of the dollars MCOs receive from the state for this care. Participating plans will also be incentivized to participate in this program and will not be expected to cover any potential losses. Washington has an opportunity to develop a similar program in its VBP efforts that are separate from the planned challenge pool and reinvestment pool funds to expedite VBP goals across the state.

Conclusion

Health care payment reform continues to evolve as a growing component of provider reimbursement from all government payment sources, as well as an increasing number of commercial payers. Thus, it is important for organizations to develop the appropriate strategies to remain financially viable in this ever-changing environment. The focus for health care will no longer be the acute care setting, but instead there will be growing trends to improve health of the population via overall care management strategies. This becomes particularly important for the Medicaid population and managed care as health care costs and patient populations continue to grow but funding does not. It is in the best interest of states and providers to identify innovative opportunities to transform health care and ensure financial sustainability. States like New York and Washington will become pioneers as they continue to take on opportunities to fund Medicaid transformation via 1115 Waiver DSRIP funds. The VBP roadmaps developed by these states and the operationalization of plans will serve as the footprint for states that take on similar challenges in the future.

COPE Health Solutions’ nationally recognized team includes experts in value-based payment methodologies and managed care contracting. Our team of experts has demonstrated success in development of contracting strategies for DSRIP funds with provider performance based payments that align with the goals of VBP for NYS. Please contact us at DSRIP@copy.laraco.net to learn more.

Footnotes:

1Himmelstein, D. U., & Woolhandler, S. (2016). The Current and Projected Taxpayer Shares of US Health Costs. Am J Public Health American Journal of Public Health, 106(3), 449-452. doi:10.2105/ajph.2015.302997

2Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountsprojected.html

3Congress.gov: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/actions

4Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html>

5https://hcp-lan.org/groups/apm-fpt/apm-framework/

6https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/waivers/1115/section-1115-demonstrations.html

7https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-state/by-state.html

8A Path toward Value Based Payment: Annual Update: June 2016 Year 2. (2016, March). Retrieved from https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/docs/1st_annual_update_nystate_roadmap.pdf

9A Performing Provider System (PPS) as defined by the NYS DSRIP Program is the entity responsible for creating and implementing a DSRIP project. The providers that make up a PPS form partnerships and collaborate in a DSRIP project plan.

10http://www.hca.wa.gov/hw/Documents/waiverappl.pdf

11 Accountable Communities of Health (ACH) as defined in the Washington State waiver application are regionally organized public-private collaboratives that form multi-sector partnerships and work together on shared health goals. They are Washington’s structured approach to incorporating social determinants of health in all aspects of health transformation across public and private payers and delivery settings.

12http://www.hca.wa.gov/hw/Documents/vbp_roadmap.pdf

13A Path toward Value Based Payment: Annual Update: June 2016 Year 2. (2016, March). Retrieved from https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/docs/1st_annual_update_nystate_roadmap.pdf

14HCA Value-based Road Map, 2017-2021 (June 14, 2016). Retrieved from http://www.hca.wa.gov/hw/Documents/vbp_roadmap.pdf